- Park Offices and Staff

- Transparent administration

- Body's Register

- Procedures and Forms

- Laws and regulations

- List of websites

- Guided itineraries

- Conferences

- Bibliography

- Park's calendar 2019

- Projects

- Research

- Materials and technical tables of the forum

- Community Service

Home » Nature and history

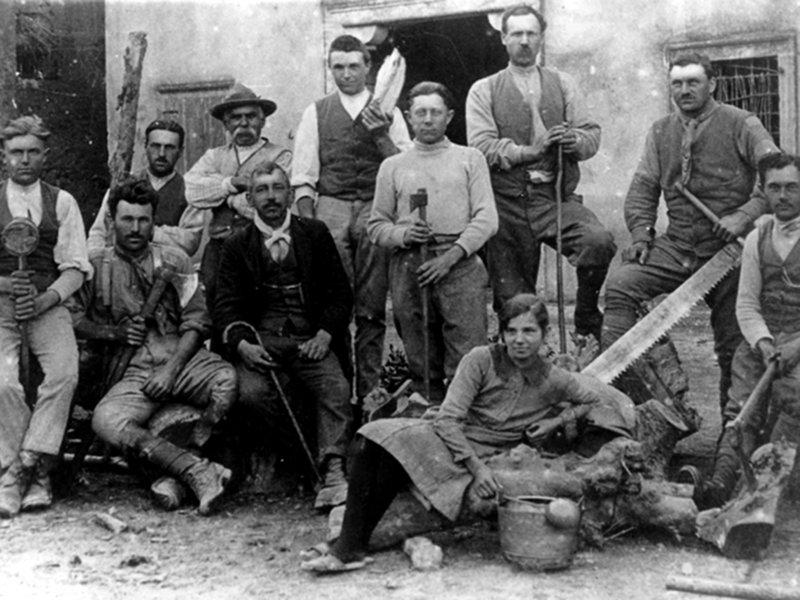

The story of a valley and its people

An uphill life

The history of mountain communities, whose survival was inextricably linked to a difficult territory and nature, is written all uphill, and not only in a figurative way. Millennia of struggle to cultivate, to move, to take indispensable resources from the mountain: stone, wood, lands to cultivate and for pastures.The verticality itself was the main element of survival: all their economy was based on seasonal altitude shifts, and on the nature rhythms. This is witnessed by the numerous terracing works destined for cultivation and a dense network of roads and paths that marked the valley slopes, connecting the valley floor to the mountain pastures.

For the Val Grande communities, the resources were particularly poor: reaching the mountain pastures could mean accompanying cattle at a time along narrow and steep paths, or collecting the little rain water in some cisterns, taking the survival from the mountain, in a daily "uphill life".

The countries that surround the valley have their origins in the Roman age, some even in the Iron Age. In addition to the numerous rock carvings and funerary objects found in the necropolis of Malesco and Miazzina, the Celtic head of Vogogna is of great importance.

In the small municipality of Dresio, inserted in a fountain dated 1753, it is possible to admire the reproduction of the so-called "grotesque", a mysterious soapstone head of Celtic tradition. The original, attributed to the second Iron Age (around 450-15 BC) and now kept in the Pretorio vogognese, is one of the most important examples of Celtic art in Piedmont. The incisions that give shape to the face, those of the forehead and the side of the eyes, as well as the large moustache still attached to the straight nose, highlight the symbolic value of the mask, whose wrinkles come together and form a tree that starts from the nose lines and reaches the arched eyebrows. Probably this exceptional testimony of the Ossola leponzia figurative culture was aimed at representing the Celtic divinity of Belenus/Apollo. Archaeological studies suggest that the mask was part of a statue placed in a sacred open area.

Before the year 1000, the Val Grande was perhaps frequented by hunters, but certainly never inhabited since it was too wild and inaccessible.

A document dated 1014 talks about "uncultivated forests" existing beyond the Colma of Premosello. The Val Grande was still called "Valdo" meaning "wood", "forest". The first shepherds took refuge in the "balme", shelters under rock of prehistoric tradition. It is between the tenth and twelfth centuries that the landscape of the valley begins to change. Forests and uncultivated lands are deforested and turned into pasture. This is how summer pastures and spring-autumn meadows are born.

From the fourteenth century, the cutting of the woods became a further source of income for the Valgrandine communities, continuing ever more intensely until the mid-1900s. Nowadays, remains of cableways, charcoal kiosks, and beeches re-grown after cutting the main trunk, are just some testimonies of the deforestation. Abandoned pastures are instead re-colonized by pioneer species such as birches: a landscape that changes its appearance from year to year.

Furthermore, an important page of the Italian Resistance was written on these mountains. In June 1944, the Val Grande and the Val Pogallo were the scene of bitter clashes between the partisan formations and the Nazi-Fascist troops. In Pogallo, a plaque commemorates 17 young partisans, some of whom were unknown, killed on 18 June 1944. In the upper Verbano area, the victims of the mopping-up operations were over two hundred, with battles and executions that culminated in Fondotoce, with the execution of 43 partisans captured in various places of the Val Grande.

Just in Fondotoce (Verbania) stands the Casa della Resistenza, an important place of memory and aggregation in order not to forget World War II and all other wars.

© 2024 - Ente Parco Nazionale Val Grande

Villa Biraghi, Piazza Pretorio, 6 - 28805 Vogogna (VB)

Tel. +39 0324/87540 - Fax +39 0324/878573

E-mail: info@parcovalgrande.it - Certified mail: parcovalgrande@legalmail.it

USt - IdNr. 01683850034

Tel. +39 0324/87540 - Fax +39 0324/878573

E-mail: info@parcovalgrande.it - Certified mail: parcovalgrande@legalmail.it

USt - IdNr. 01683850034